and the 78th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising

A short speech on the subject of Polish war anniversaries given at the ceremony to mark the start of the school year at the Polish Alma Mater in Los Angeles. My speech is in Polish, so I decided to create an English translation and add some poems.

Dear children, ladies and gentlemen, As Vice President for Public Affairs of the Polish American Congress in California, I am to remind you all of important historical anniversaries related to the month of September.

On September 1, we celebrate the anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War. This year it is already the 83rd. One might ask, after more than 80 years, why should we care about this? Why must we remember? Why is Poland covered with monuments to those murdered during the war? Why do refuse to forget this national tragedy? When I was telling my youngest son about the war, still in elementary school, he said to me: "Mom, why are you telling me about this, it is not important, if it were important, they would write about it in my American textbooks..." Luckily, he changed his mind. But the fact is: they did not write and do not write about this. So, we have to remember.

As Poles in exile, those who emigrated from the country, and those already born here, that is, the second and third generation of the Polish diaspora, we must remember the history of our first homeland. The Second World War is a huge tragedy for the Polish nation. Poland was attacked by the Germans on September 1, 1939, on many fronts simultaneously, with provocations, when the Germans disguised prisoners in Polish uniforms and killed them as if in battle; to lie to the world that it was Poland that attacked Germany first. Now these historic frauds are called "false flags." Poland defended itself desperately, but it fell when stabbed in the back: on September 17, 1939, the country was divided between the two occupiers, the Soviet Union and Germany.

During the war, over 6 million people died in Poland, more than one fifth or 22% of the country's population. Of each 1000 residents of the country, 220 died during the war; in comparison, Great Britain lost 8 and France 15. The second country most affected was the Soviet Union with 115 residents killed out of each thousand. Everyone in America knows that about 2.7 million Polish Jews died in the Holocaust; but the losses of Slavs in Poland were higher: 2,770,000 people died only on territories occupied by the Germans. They were mainly Catholics. The first prisoners of Auschwitz KL were Polish Slavs, Catholics. Among them were my mother's uncles, two Catholic priests from the Wajszczuk family, first sent to Auschwitz KL, and then to Dachau, where the clergy was imprisoned.

Let us add to this the huge number of people murdered and displaced by the Soviets, deported from the Eastern Borderlands (what is now western Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania) to Siberia or Kazakhstan, where another million people died. In the Borderlands, "Kresy," about 3.5 million people lost their homes, farms, estates, businesses… Everything except their lives. This was the story of my grandparents and my mother from Baranowicze, now in Belarus, as well as of the whole family from the vicinity of Nowogrodek and Lake Switez, where Polish national bard, Adam Mickiewicz, was born and raised. I wrote about this in a short article dedicated to gold heirlooms my Mom left for me: https://polishamericanstudies.org/text/181/wajszczuk-gold.html. Another story about the brave women of my extended family and their resilience during and after the war appeared on this blog: http://chopinwithcherries.blogspot.com/2021/01/portraits-of-survivors-babcia-prababcia.html.

We must all remember about Poles deported to Siberia, because in America we do not hear about them. I dedicated a book of poems to some of the victims and survivors, entitled The Rainy Bread ... My mother's aunt Irena De Belina, saved as an orphan from Siberia by Anders' army, ended up in Chicago via Iran and Switzerland. In her old age in Albuquerque, New Mexico, she told schoolchildren about the war hunger, how her parents died in a gulag . There are many such stories in our communities. I wrote two poems about her, the first one is below, with a lesson about food and war-time hunger:

≡ PEELING THE POTATOES ≡

~ for Grandma Maria Wajszczuk, neé Wasiuk (1906-1973)

Her Grandma showed her how to hold

the knife, cut a straight, narrow strip,

keeping the creamy flesh nearly intact,

ready for the pot of boiling water.

Don’t throw away any food. The old refrain.

My sisters, Tonia and Irena lived on potato peels

in Siberia. She is confused. She knows

Ciocia Tonia — glasses on the tip of her nose,

perfectly even dentures — but Irena? Who is that?

They were all deported to Siberia. Not sure how

Irena’s parents died — of typhus, or starvation, maybe?

They used to pick through garbage heaps,

look for rotten cabbage, kitchen refuse

to cook and eat. They cooked and ate anything

they found under the snow, frozen solid.

The water’s boiling. Babcia guides her hand:

You have to tilt the cutting board

toward the pot, slide the potatoes in.

Don’t let them drop and splash you.

What happened next? The orphaned children

went with the Anders’s Army and the Red Cross

to Iran, Switzerland, Chicago. The kitchen

fills with memories. Mist above the stove.

Grandma piles up buttery, steaming,

mashed potatoes on her plate. Eat, child, eat.

Ten years later, Aunt Irena came to visit.

She looked like Grandma, only smaller.

Her legs were crooked.

The crooked legs of Aunt Irena were due to starvation and lack of sunlight in childhood, she had rickets in Siberia. At least, she survived. So did the mother of Director of the Oral Archives of the former inhabitants of the eastern Borderlands at the Historical Museum of Warsaw, Jan Jakub Kolski. When he told her story at the meeting of the Kresy-Syberia Association in Warsaw in 2016, I wrote the following poem.

≡ A SONG FOR A KEY ≡

~ for Jan Jakub Kolski and his Mother

This is a key.

This is an iron key.

This is a large, iron key.

This is an old, large, iron key.

A key my mother carried in her purse.

This is an old, large, wrought-iron key my mother

carried in her purse every single day.

This is a field.

This is a flat field.

This is a flat, empty field.

This is a flat, empty field in the Ukraine

that used to be Poland. A flat, empty field

where my mother’s house once stood, surrounded

by a tall wooden fence with a tall wooden gate,

and a solid, large, wrought-iron lock.

They told her: pack!

They told her: go!

They told her: out!

You do not belong.

This is our land.

There is not house.

There is no fence.

There is no gate.

This is the key.

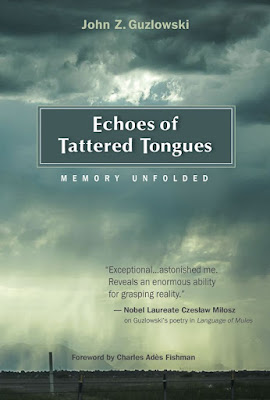

"Some books take a lifetime to write, yet they can be read in one sleepless night, filled with tears of compassion and a heaviness of heart. John Z. Guzlowski’s book of poetic memoirs is exactly such a book: an unforgettable, painful personal history, distilling the horrors of his parents’ experiences in German labor and concentration camps into transcendent artwork of lucid beauty. [...] It is only through this gradual unveiling of the depth of suffering inflicted on Guzlowski’s mother and father, that we become aware of the historic forces that forged their fates, brought them together, and impacted their son so severely that he spent the past thirty years obsessively writing about his parents’ war-time ordeal and its post-war consequences, as if there were no other topics worthy of his pen.[...] The inmates were dehumanized in the German camps, they became animals or plants: the mother – a suffocating dog, the father – “a bony mule with the hard eyes / one encounters in nightmares or in hell” (“What a Starving Man Has”). In Buchenwald and other camps, Guzlowski’s father and his fellow inmates were like mules carrying heavy loads, and dying of exhaustion:

“These men belonged to the Germans

the way a mule belonged to the Germans

and the Germans stood watching

their hunger and then their deaths,

watched them as if they were dead trees

in the wind, and waited for them to fall,

and some of the men did…”

While being tortured and abused, Guzlowski’s father thought of what he could not say to the inexplicably cruel guards: “Sirs, we are all / brothers and if this war ever ends, / please, never tell your children / what you’ve done to me today.” (“The Work my Father did in Germany”). He was right, they did not tell… Indeed, these crimes were largely forgotten, Germany was rebuilt with American help, while the German concentration camps were renamed “Polish concentration camps” in a revisionist twist, Goebbels-style."

A profound trauma, like that of the Guzlowski family, takes years to heal. It is as if the whole Polish nation still suffers from the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder - the negativity, aggression, anger and outbursts at others are a superficial proof of that. Wounded animals lash out at everyone approaching them. Wounded people get angry and hostile for no apparent reason... But let us return to our story.

Let us remember that until 1989, until the first free elections and the end of the Polish People's Republic, there was the Polish Government of the Second Republic in London. The second, because the First is the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, enslaved for 123 years of partitions by Russia, Prussia and Austria. We remember it on May 3, on the Constitution Day. The Second Republic of Poland survived only 20 years from the end of the First World War in 1918. On November 11, we celebrate Independence Day.

We can be proud that Poland is the only country in Europe that did not have a collaborator government that cooperated with Germany! During the war, in occupied Poland, the Polish Home Army did not lay down their arms, around 400,000 people, mostly young people, belonged to underground troops. The Home Army trained them in hiding. At home, young people learned Polish, history, literature, and traditions. The underground activities were vast; they included academic lectures and private concerts of Chopin's music, which was forbidden by the Germans. Chopin's monuments were also destroyed. The time of war in Poland was hard, poor, full of hunger, disease and trauma.

Yet, Poles have a talent for survival. They mobilize in crisis. Their slogan: God, Honor, Homeland motivates them to action. And so, on August 1, 1944, the badly unarmed, poorly trained young inhabitants of Warsaw went into battle. The Soviet army had already entered the territories of Polesie near Lublin and Mazowsze to Vistula; they were already approaching Warsaw. If the country's capital could be liberated and the government from London could return, Poland could have really regained independence.

Unfortunately, Stalin mailed other plans. He had previously arranged them with Churchill, Prime Minister of England and with the American President Roosevelt. As early as 1943, they gave up power to rule over Poland and other countries to Soviet Russia in secret agreements in Yalta and Tehran. Poles in Warsaw did not know anything about it when they commenced their heroic battle 78 years ago.

Their sacrifice and courage are indescribable. The Warsaw Uprising lasted until October 2, for as long as 63 days. It ended with a defeat. The losses of the Polish civilian and military population were enormous; up to 18,000 soldiers died in battles and about 200,000 civilians were killed. We should honor their memory.

This devastating fight for freedom so enraged the German authorities, that Hitler ordered the city to be completely demolished and all inhabitants to be deported. Soviet troops waited on the other bank of the Vistula until Warsaw bleeds out. The so-called "liberation" did not come until January 17, 1945, when the Russians entered the empty ruins.

On my way to school in Warsaw, every day I walked past three monuments with the inscriptions "Site made sacred by the blood of Polish victims" and our school building had round holes from bullets on its thick gray walls. I commemorated the walk to school in a poem:

≡ THE WAY TO SCHOOL ≡

Walking to her high school on Bema Street.

she counted three cement crosses in ten minutes

every morning.

One in the middle of her subdivision of apartment blocks,

standing guard at the edge of chipped asphalt:

Four hundred.

One in the mini-park, where two gravel paths cross

on a patch of overgrown grass after you go under the train bridge:

Nine hundred.

One on the wall of a grimy three-story building,

with round bullet holes still visible in the stained, grey stucco:

Twenty-two hundred.

She memorized the inscriptions: “This place is sanctified

by the blood of Poles fighting for freedom, murdered by Hitlerites.”

“Some Germans were good, not Nazis,” her teacher said,

“They marched in the May 1st parades.”

Only the numbers differed, and dates:

August 5, August 6, August 7, 1944. The Uprising.

50 thousand civilians shot in the streets of Warsaw.

The bullets came fast. Those soldiers had practice.

Wehrmacht, Police Batalions, RONA, Waffen SS.

No shortage of killers. Some had children back home.

She did not want to think of thousands.

She did not want to know their names.

While I commuted to the music school in the rebuilt Old Town of Warsaw in the 1970s, I could see the remains of the royal palace: a piece of the last wall with a window hole through which the moon would peek... The castle was beautifully rebuilt - this painstaking and meticulous project lasted for 20 years. So we can say that the cure for war is peace, the cure for destruction is creation. But it is easy to destroy something, and much harder to rebuild.

Was it worth it? Historians' discussion continues as we praise the heroes 78 years after their tragic struggle. Among us in California is Professor Andrzej Targowski, a child of the Uprising. He says that the uprising was a grave mistake, because the losses were too extensive, both human and material. The city's inhabitants were murdered. The buildings, libraries and museums were dynamited and burned down. Had the Uprising not taken place, 200,000 inhabitants of Warsaw would have had a chance of survival. And in a nation's crisis, survival is paramount. It's easy to die, dreaming of glory. It's harder, smarter, to survive, keep the traditions quietly, at home, to pass the memory on to the next generations.

How important is this memory today, when Polish Slavic history is not found in American textbooks. So let us remember: who we are, where we came from, where we are going. Let studying in a Polish school fill us with pride in our traditions, in our great history. Let this experience teach us to build and create, to work selflessly in community organizations, and to help others.

On behalf of the Polish American Congress, I wish all children and youth a wonderful and fruitful school year. And no matter what, let's not forget to laugh. Let me end this article with a poem about the Warsaw Uprising Survivor, my Mom's friend:

≡ PANI BASIA ≡

~ in memoriam Barbara Wysocka, “Irma” soldier in the Warsaw

Uprising, prisoner of Stutthof Camp (1927-1997)

Who was this stranger at Christmas Eve dinners?

A tall, stern lady who did not smile or talk to children.

Distinguished. Distant. Too stiff for hugging.

She looked at us as if from another planet.

She ate her food slowly, methodically,

relishing each sip of the hot beet soup,

gingerly picking fishbones out of carp in aspic.

An aura of loneliness spread out around her.

Why did Mom take her for vacation to Abu Dhabi,

on an exotic adventure, to see red sands, palms, camels?

The answer waited for decades in packets

of old letters, medals earned during the war.

She was “Irma,” a teen liaison for Division Baszta

in Mokotów. Fought to the end, Warsaw’s fall.

Imprisoned in the Stutthof Concentration Camp.

Her whole family perished. All alone.

Never married. Wrapped in her grief

like a cashmere shawl.

On her vacation in Persian Gulf, she saw

wobbly camels race – and finally laughed.

No comments:

Post a Comment