During my summer travel to Poland and two conferences on emigration, in Krakow and Gdansk, I met with my academic mentor and advisor, Prof. Zofia Helman of the University of Warsaw. After a light lunch at the faculty club in Kazimierzowski Palace, she promptly took me shopping to the Prus Bookstore across the Krakowskie Przedmiescie street. My box of books on music has recently arrived with three biographical treasures about Chopin's family and circle of friends:

1. Rodzina Matki Chopina: Mity i Rzeczywistosc [The Family of Chopin's Mother - Myths and Reality], by Andrzej Sikorski and Piotr Myslakowski (Warszawa, Studio Wydawnicze Familia, 2000)

2. "Rodzina Ojca Chopina: Migracja i Awans" [The Family of Chopin's Father - Migration and Ascent] by Piotr Myslakowski (Warszawa, Studio Wydawnicze Familia, 2002)

3. "Chopinowie: Krag Rodzinno-Towarzyski" [Chopins - The Familial-Social Circle] by Piotr Myslakowski and Andrzej Sikorski (Warszawa, Studio Wydawnicze Familia, 2005).

The three books, available only in Polish, are based on decades of intense archival studies by the authors, as well as reports from archival studies by other scholars. They include numerous transcripts and translations of archival documents and debunk myths about the origins and upbringing of Fryderyk Chopin, the scion of French and Polish families that could be described as "lower middle class" today.

The French heritage of Chopin's father, Nicolas, was questioned by patriotic mythmakers in the past. Ideas that he was a descendant of Polish soldiers who settled in France were circulated at the end of the 19th century. Piotr Myslakowski shows conclusively that this, widely abandoned myth, had no grounds in facts. He also reveals surprises in Chopin's lineage. His forefather moved from a small Alpine village of smugglers living in abysmal poverty to lower, border area of France that used to be a part of the kingdom of Lotharingia and is now called Lorraine region.

Apparently, the great-great-...-grandfather of Chopin left the home village and never looked back. From the underclass of smugglers the family rose to the lower class of peasants and artisans in the village. One of the Lorraine great-great-grandfathers of Chopin became a wheel-maker and a scribe, rising to a position of note in the community. His descendant, Nicolas, left his family behind at the age of 17 when he moved to Poland where he became first a live-in tutor of sons of noble families, and then a school professor and principal. In one step after another, the family rose from murky and far-less-than-respectable background through hard work, education, and the pursuit of virtues and moral values. The subsequent generations of Chopins in the three locations did not stay in touch. When the artistocrat-of-the-spirit Chopin moved to Paris to hobnob with princesses, he did not look up his aunts and cousins in Lorraine. They were peasants, he was a friend of aristocrats. They had nothing in common. His ample correspondence with his family shows intense affection for members of his immediate familial circle. But he had no interest, nor need to reach out beyond.

Similarly, the family of his mother came from humble roots. Not as humble as the French family: her kin were among impoverished gentry who often disappeared from historical records, as they did not own land or estates. The two scholars traced their history through the records of baptisms - the Krzyzanowski family members could be Godfathers or Godmothers to various children where they lived. Another lively and surprising source of family history was found in the court records of the warring, lawless "less-than-noble" members of the Polish landed gentry, whose pastime, it seems, was to sue each other and, in an absence of an execution of the sentence, raid their enemies and attack, injure or even kill them, while destroying or stealing their possessions. As an employee of such a brigand-noble, one of Justyna Krzyzanowska's forebearers is noted in several court records of this kind. Fascinating reading!

I have not yet started reading the "family circle" part of the three books, but I believe that it would be to the benefit of English-speaking Chopin lovers and scholars to have access to their English translations. The books are written in a very engaging and engrossing fashion. I read the story about Chopin's father as if it were a murder mystery - and, in fact, a mystery solved it is. The sooner we have English versions, the better for all future scholars of Chopin's life and music.

Looking for Chopin and the beauty of his music everywhere - in concert halls, poetry, films, and more. In 2010 we celebrated his 200th birthday with an anthology of 123 poems. Here, we'll follow the music's echoes in the hearts and minds of poets and artists, musicians and listeners... Who knows what we'll find?

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Chopin's Prelude and the Prometheus, or Music vs. Aliens (Vol. 3, No. 8)

Of all the preludes by Chopin, the one in D-flat Major, op. 28 no. 15, known as the "Raindrop" prelude, has attracted the most attention - among the poets and filmmakers, at least. . . I think it is because it is relatively easy to play; even I could learn it! And I was known in my music-making days as having two left hands on the keyboard. ..

In any case, this sublime melody (or rather, the sostenuto themes appearing in the A-sections of the ABA form) has recently been used in a new sci-fi film by Ridley Scott, "Prometheus." This pre-quel to the alien trilogy, focuses on the attempts of totally evil, poisonous alien creatures, both grossly slimy and supremely intelligent, to take over and destroy humanity.

Apparently, Ridley Scott has loved this melody for a long time and decided to use it both in the film and in the final credits as a symbol of what matters. Chopin's miniature becomes here the most delicate sign of our shared humanity, threatened and attacked by unbearable screeches of the alien life-killing life forms. [An account loosely based on an article in the Los Angeles Times, July 6, 2012]

_______________________________

Let's listen to the Prelude played by pianists who did not have two left hands:

Arthur Rubinstein: Prelude in D-flat Major, op. 28 no. 15, a tad too fast to my taste...

Martha Argerich: Prelude in D-flat Major, op. 28 no. 15, with amazing rubatos!

Maurizio Pollini; Prelude in D-flat Major op. 28 no. 15, this one is a concert encore, a great way to end an evening...

________________________________

The "Raindrop" Prelude has been surrounded by stories and legends since its creation. Chopin wrote some of it during the fateful stay in the Monastery on the island of Mallorca, the city of Valldemosa in 1834. He got really sick and was suffering from hallucinations, nausea, and fevers. Some modern scholars claim that these were the symptoms of his poisoning with carbon monoxide, from a heater he had in the closed space of the cold cell where he was composing all day.

George Sand wrote in her Histoire de ma vie that Chopin had a very peculiar vision or dream, while playing the piano and working on this prelude:

He saw himself drowned in a lake. Heavy drops of icy water fell in a regular rhythm on his breast, and when I made him listen to the sound of the drops of water indeed falling in rhythm on the roof, he denied having heard it. He was even angry that I should interpret this in terms of imitative sounds. He protested with all his might – and he was right to – against the childishness of such aural imitations. His genius was filled with the mysterious sounds of nature, but transformed into sublime equivalents in musical thought, and not through slavish imitation of the actual external sounds."

__________________________________

Before the cosmic battle of Ridley Scott's aliens, film-makers used the Prelude in a variety of contexts, as listed on Wikipedia by anonymous sribes (thanks for all the work!):

The raindrop prelude is also featured on the soundtrack of the 1996 Australian film Shine about the life of pianist David Helfgott.

The prelude appears in the "Crows" section of Akira Kurosawa's film Dreams.

The prelude plays a pivotal role in the 1990 film version of Captain America. The piece is played at a childhood piano recital by the young prodigy who would become the Red Skull, and a recording of this incident is later played by the titular hero to delay the now-70-year-old Red Skull from detonating a nuclear bomb that would destroy all of Southern Europe, the detonator for which was also concealed in a grand piano.

The dramatic bridge of the prelude was used in an elaborate pre-release commercial for the video game Halo 3 as a part of the $10 million "Believe" ad campaign. The piece plays over close-up footage of a highly detailed diorama of an historically pivotal battle in the game's universe.

The piece appears in the John Woo film Face/Off in a seduction scene between Castor Troy and Eve Archer.

The prelude appears in the fantasy video game Eternal Sonata, where Chopin's music plays a major part.

The piece is studied as a 'Set Work' in the English exam board Edexcel's GCSE in Music.

The piece is used in the film Margin Call, as Kevin Spacey's character sleeps in his office but is then woken up by the prelude's climax.

The prelude is used in the English trailer for the Japanese film Battle Royale.

In addition, a music blog, The World's Greatest Music, mentions yet another TV appearance of Chopin's Prelude, in the credits of a 1980s show, Howard's End.

If you know of more ways to "kill" this perfectly beautiful piece of music, let me know...

__________________________________

The Prelude No. 15 has long been a favorite of poets. In the anthology "Chopin with Cherries," there are no fewer than ten poems inspired by or mentioning this particular prelude. Christine Klocek-Lim goes back to the story by George Sand.

Prelude in Majorca

Christine Klocek-Lim

The wet day carried rain into night

as he composed alone.

With each note he wept

and music fell on the monastery,

each note a cry for breath

his lungs could barely hold.

Even as his world

dissolved around him

“into a terrible dejection,”

he played that old piano in Valldemosa

until tuberculosis didn’t matter;

until the interminable night

became more than a rainstorm,

more than one man sitting alone

at a piano, waiting

“in a kind of quiet desperation”

for his lover to come home

from Palma.

When Aurore finally returned

“in absolute dark”

she said his “wonderful Prelude,”

resounded on the tiles of the Charterhouse

like “tears falling upon his heart.”

Perhaps she is right.

Or perhaps Chopin “denied

having heard” the raindrops.

Perhaps in the alone

of that torrential night

he created his music simply

to hold himself inside life

for just one note longer.

Notes:

Prelude No.15 in D-flat Major, Op. 28. Quotes from Histoire de Ma Vie (History of My Life, vol. 4) by George Sand (Aurore, Baronne Dudevant).

_______________________________

Another contemporary poet, Carrie Purcell thought about her music lessons...

Prelude in D-Flat Major, Opus 28, No. 15

Carrie A. Purcell

You have to

my teacher said

think of that note like rain,

steady, but who,

my teacher said

wants to hear only that?

On Majorca in a monastery

incessant coughing

covered by incessant composition

and everywhere dripping

sotto voce

move the rain lower

let it fill the space left in your lungs

let it triumph

We die so often

we don’t call it dying anymore

In any case, this sublime melody (or rather, the sostenuto themes appearing in the A-sections of the ABA form) has recently been used in a new sci-fi film by Ridley Scott, "Prometheus." This pre-quel to the alien trilogy, focuses on the attempts of totally evil, poisonous alien creatures, both grossly slimy and supremely intelligent, to take over and destroy humanity.

Apparently, Ridley Scott has loved this melody for a long time and decided to use it both in the film and in the final credits as a symbol of what matters. Chopin's miniature becomes here the most delicate sign of our shared humanity, threatened and attacked by unbearable screeches of the alien life-killing life forms. [An account loosely based on an article in the Los Angeles Times, July 6, 2012]

_______________________________

Let's listen to the Prelude played by pianists who did not have two left hands:

________________________________

The "Raindrop" Prelude has been surrounded by stories and legends since its creation. Chopin wrote some of it during the fateful stay in the Monastery on the island of Mallorca, the city of Valldemosa in 1834. He got really sick and was suffering from hallucinations, nausea, and fevers. Some modern scholars claim that these were the symptoms of his poisoning with carbon monoxide, from a heater he had in the closed space of the cold cell where he was composing all day.

George Sand wrote in her Histoire de ma vie that Chopin had a very peculiar vision or dream, while playing the piano and working on this prelude:

He saw himself drowned in a lake. Heavy drops of icy water fell in a regular rhythm on his breast, and when I made him listen to the sound of the drops of water indeed falling in rhythm on the roof, he denied having heard it. He was even angry that I should interpret this in terms of imitative sounds. He protested with all his might – and he was right to – against the childishness of such aural imitations. His genius was filled with the mysterious sounds of nature, but transformed into sublime equivalents in musical thought, and not through slavish imitation of the actual external sounds."

__________________________________

Before the cosmic battle of Ridley Scott's aliens, film-makers used the Prelude in a variety of contexts, as listed on Wikipedia by anonymous sribes (thanks for all the work!):

- In the 1979 James Bond movie Moonraker, villain Sir Hugo Drax plays the Raindrop Prelude in his chateau on a grand piano when Bond comes to visit.

If you know of more ways to "kill" this perfectly beautiful piece of music, let me know...

__________________________________

The Prelude No. 15 has long been a favorite of poets. In the anthology "Chopin with Cherries," there are no fewer than ten poems inspired by or mentioning this particular prelude. Christine Klocek-Lim goes back to the story by George Sand.

Prelude in Majorca

Christine Klocek-Lim

The wet day carried rain into night

as he composed alone.

With each note he wept

and music fell on the monastery,

each note a cry for breath

his lungs could barely hold.

Even as his world

dissolved around him

“into a terrible dejection,”

he played that old piano in Valldemosa

until tuberculosis didn’t matter;

until the interminable night

became more than a rainstorm,

more than one man sitting alone

at a piano, waiting

“in a kind of quiet desperation”

for his lover to come home

from Palma.

When Aurore finally returned

“in absolute dark”

she said his “wonderful Prelude,”

resounded on the tiles of the Charterhouse

like “tears falling upon his heart.”

Perhaps she is right.

Or perhaps Chopin “denied

having heard” the raindrops.

Perhaps in the alone

of that torrential night

he created his music simply

to hold himself inside life

for just one note longer.

Notes:

Prelude No.15 in D-flat Major, Op. 28. Quotes from Histoire de Ma Vie (History of My Life, vol. 4) by George Sand (Aurore, Baronne Dudevant).

_______________________________

Another contemporary poet, Carrie Purcell thought about her music lessons...

Prelude in D-Flat Major, Opus 28, No. 15

Carrie A. Purcell

You have to

my teacher said

think of that note like rain,

steady, but who,

my teacher said

wants to hear only that?

On Majorca in a monastery

incessant coughing

covered by incessant composition

and everywhere dripping

sotto voce

move the rain lower

let it fill the space left in your lungs

let it triumph

We die so often

we don’t call it dying anymore

Friday, June 8, 2012

On Hypnotic Modernism of Maciej Grzybowski (Vol. 3, No. 7)

How can you tell if a pianist is good enough to be worth the effort of driving on our congested freeways to attend his concert on a Friday night, if you have never heard his name before? Hard to tell… perhaps, you should believe what others say about him. You certainly should watch for the name of Maciej Grzybowski, an extraordinary Polish pianist, who recently visited Los Angeles upon the invitation of the Helena Modjeska Art and Culture Club. On May 11, 2011, he performed a solo piano recital at the First Presbyterian Church in Santa Monica. From there, he went on to play for the Polish Arts and Culture Club of San Diego and then to appear in a recital in Montreal, Canada. (In the interest of full disclosure, I have to state that as the President of the Modjeska Club I personally invited him to L.A., while his tour was sponsored by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute of Poland and supported by the Polish Consulate in Los Angeles).

The specially crafted Santa Monica program included music by Polish composers (Paweł Mykietyn, Witold Lutosławski, Paweł Szymański, and Fryderyk Chopin) juxtaposed with Western classics – Johannes Brahms, Claude Debussy, and Maurice Ravel. Some of the best music of the world, played by one of the best pianists you can ever hear…

Born in 1968 and educated in Warsaw, Maciej Grzybowski is the winner of the First Prize and the Special Prize at the 20th Century Music Competition for Young Performers in Warsaw (1992). He made numerous phonographic, radio and television recordings as a soloist and chamber musician and collaborated with Sinfonia Varsovia conducted by such conductors as Jan Krenz, Witold Lutosławski and Krzysztof Penderecki. From 1996 to 2000 Grzybowski was a co-director of the "NONSTROM presents" concert cycle in Warsaw. He took part in numerous music festivals in Poland, such as the Warsaw Autumn, Musica Polonica Nova, Witold Lutosławski Forum, Warsaw Musical Encounters, and the Polish Radio Music Festival. He also performed at the Biennial of Contemporary Music in Zagreb, Hofkonzerte im Podewil, Berlin and festivals in Lvov, Kiev, and Odessa (Ukraine). In March 2005, Grzybowski’s recital at the Mozart Hall in Bologna was recognized as the greatest music event of the 2000s. After Grzybowski’s U.S. debut in New York, in August 2006 EMI Classics released his second solo CD with works by Paweł Szymański (b. 1954). He also appeared in three concerts at the critically acclaimed Festival of Paweł Szymański's Music in Warsaw. In February 2008, Grzybowski premiered a Piano Concerto by an unjustly forgotten composer, Andrzej Czajkowski (Andre Tchaikovsky).

After the 2004 release of Grzybowski’s first solo CD, Dialog, juxtaposing works by Johann Sebastian Bach, Alban Berg, Pawel Mykietyn, Arnold Schönberg and Pawel Szymanski, (Universal Music Polska), critics raved:

· “His interpretations of Bach, Berg, Schönberg, Szymański and Mykietyn show the touch of genius! There are certainly none today to equal his readings of Bach! (...) How refreshing and exciting it is to be in the presence of such great art of interpretation, akin to a genius!” (Bohdan Pociej).

· “The performance of Berg’s youthful Sonata and Schönberg’s Sechs kleine Klavierstücke could easily stand alongside the recordings of Gould or Pollini.” (Marcin Gmys).

These exorbitant expressions of praise were seconded by attendees of the Santa Monica recital including composer Walter Arlen, the founder of the music department at Loyola Marymount University and for 30 years the most influential music critic of the Los Angeles Times. After the concert, he stated, “this was the best pianist I have ever heard in my life.” His praise was seconded by another listener, Howard Myers: “Maciej is a phenomenon, a marvel, a miracle, a special kind of genius.” The belief in Grzybowski’s exceptional talent is shared by the Director of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, Paweł Potoroczyn: “He is more than just a talented pianist – he is both a virtuoso of the highest order and a great musical personality. The resultant unique combination is that of an uncommon musical genius that fully justifies comparing him with such masters as Glenn Gould or Maurizio Pollini.”

While admitting to a personal bias towards someone who has dedicated years of his life to the music of Paweł Szymański, one of the greatest Polish composers who ever lived (as it will become apparent in 50 years, when the dust settles and musical diamonds will be found in the sea of ashes), I had no doubt that by bringing Maciej Grzybowski to California, I offered our audiences a special treat. His recital exceeded even my already sky-high expectations. First the program: arranged in two distinct parts, pairing composers of different generations in a surprising dialogue of musical ideas.

The youngest of the composers featured by Grzybowski was Paweł Mykietyn (b. 1971), his colleague and co-founder of the Nonstrom Ensemble where he has played the clarinet. In an entry on the Polish Music Information Center’s website affiliated with the Polish Composers’ Union, Mykietyn’s style is described in the following way: “The composer ostentatiously applies the major-minor harmonies, introducing tonal fragments interspersed with harmonically free sections. He also makes use of traditional melodic structures, transforming them in his own individual manner. Mykietyn could be described as a model postmodernist, deriving his inspiration as well as material from all the available sources without any inferiority complex.” These words could well be applied to the virtuosic and wistful Four Preludes (1992) that opened the program with their contrasting moods, textures and tempi.

|

| Grzybowski with Howard Myers and Prof. Walter Arlen. |

Under Grzybowski’s fingers, these charming miniatures sparkled with a caleidoscope of colors and rhythms. The pianist brought out the complexity of inner voices in seemingly simple pieces and endowed folk melodies with an aura of nostalgia and drama. In a stroke of genius, Grzybowski followed the folk arrangements with an entirely hypnotic and modernist reading of Drei Intermezzi, Op. 117 by Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). A standard in every music theory textbook on Schenkerian analysis, Drei Intermezzi could be heard as small interludes only in comparison with Brahms’s majestic symphonies. Composed in 1892, the intermezzi (No. 1 in E-flat major, No. 2 in B-flat minor and No. 3 in C-sharp minor) transverse cosmic landscapes of feeling evoked in Rainer Maria Rilke’s timeless poem, An Die Musik.

Yet it was the piece that followed, Two Etudes by Paweł Szymański(1954), written in 1986 and available on two Grzybowski CDs, that elicited the greatest enthusiasm of the audience. It is a work of genius, unparalleled in music in its hypnotic effect on the listeners. The Etudes, played without a break, contrast the slow emergence of music in the first etude with the titanic flows of sound in the second. The piece arises from silence in what appears to be a series of random, repeated notes and chords, but there is nothing random in Szymański’s music, everything is carefully constructed. Sometimes called a “neo-Baroque” composer (due to his frequent inspirations with the music of that period, and talent for creating complex polyphony), Szymański refers to his style as “sur-conventionalism” and thus describes his main approach: “The modern artist, and this includes composers, finds himself tossed within two extremes. If he chooses to renounce the tradition altogether, there is the danger of falling into the trap of blah-blah; if he follows the tradition too closely, he may prove trivial. This is the paradox of practicing art in modern times. What is the way out? However, there are many methods to stay out of eclecticism despite playing games with tradition. An important method for me is to violate the rules of the traditional language and to create a new context using the elements of that language." Thus, Szymanski draws from traditional tonal and harmonic language by playing with the conventions of musical styles and with the listeners’ expectations. This game of cat-and-mouse was apparent in the stretching and constricting of time in the two Etudes. The irregularity of recurring chords and notes piqued the listeners’ interest and intensified their expectations. Thus, the music grew and expanded in scope in the first Etude, to reach monumental proportions and then dissolve in massive complexities of the second.

Yet it was the piece that followed, Two Etudes by Paweł Szymański(1954), written in 1986 and available on two Grzybowski CDs, that elicited the greatest enthusiasm of the audience. It is a work of genius, unparalleled in music in its hypnotic effect on the listeners. The Etudes, played without a break, contrast the slow emergence of music in the first etude with the titanic flows of sound in the second. The piece arises from silence in what appears to be a series of random, repeated notes and chords, but there is nothing random in Szymański’s music, everything is carefully constructed. Sometimes called a “neo-Baroque” composer (due to his frequent inspirations with the music of that period, and talent for creating complex polyphony), Szymański refers to his style as “sur-conventionalism” and thus describes his main approach: “The modern artist, and this includes composers, finds himself tossed within two extremes. If he chooses to renounce the tradition altogether, there is the danger of falling into the trap of blah-blah; if he follows the tradition too closely, he may prove trivial. This is the paradox of practicing art in modern times. What is the way out? However, there are many methods to stay out of eclecticism despite playing games with tradition. An important method for me is to violate the rules of the traditional language and to create a new context using the elements of that language." Thus, Szymanski draws from traditional tonal and harmonic language by playing with the conventions of musical styles and with the listeners’ expectations. This game of cat-and-mouse was apparent in the stretching and constricting of time in the two Etudes. The irregularity of recurring chords and notes piqued the listeners’ interest and intensified their expectations. Thus, the music grew and expanded in scope in the first Etude, to reach monumental proportions and then dissolve in massive complexities of the second.  The second half of the recital started with a series of unusual readings of Fryderyk Chopin’s four mazurkas (in A Minor, Op. 7, No. 2; E Minor, Op. 41, No. 1; F Major, Op. Posth. 68, No. 3; G-sharp Minor, Op. 33, No. 1). The originality of the pianist’s interpretations rendered these well-known gems of the repertoire almost unrecognizable. More angular and modernist than usual were also three Preludes from the second volume of impressionistic masterpieces by Claude Debussy (1862-1918): II ... Feuilles mortes, VI ... „General Lavine” eccentric; VII ... La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune. These terraces were lighted less by effervescent moonlight than by the brilliant focused light of Grzybowski’s intellect. Again, they were so different from what I was used to hearing that I would need to hear these preludes again, to render an opinion. Yet, the rest of the audience was hypnotized into a complete silence and immobility: no slow, tortuous opening of candy wrappers at this recital!

The second half of the recital started with a series of unusual readings of Fryderyk Chopin’s four mazurkas (in A Minor, Op. 7, No. 2; E Minor, Op. 41, No. 1; F Major, Op. Posth. 68, No. 3; G-sharp Minor, Op. 33, No. 1). The originality of the pianist’s interpretations rendered these well-known gems of the repertoire almost unrecognizable. More angular and modernist than usual were also three Preludes from the second volume of impressionistic masterpieces by Claude Debussy (1862-1918): II ... Feuilles mortes, VI ... „General Lavine” eccentric; VII ... La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune. These terraces were lighted less by effervescent moonlight than by the brilliant focused light of Grzybowski’s intellect. Again, they were so different from what I was used to hearing that I would need to hear these preludes again, to render an opinion. Yet, the rest of the audience was hypnotized into a complete silence and immobility: no slow, tortuous opening of candy wrappers at this recital!  |

| Grzybowski with the Modjeska Club Board |

After a well-deserved standing ovation, the pianist relented and added a melancholy and thoroughly modern version of a Scarlatti’s sonata as an encore to the evening’s inspired and inspiring program. One thing is certain: the name recognition problem mentioned at the beginning should be resolved, once for all, in the case of Maciej Grzybowski: just go to every concert of his, and if you cannot go, buy his CDs.

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Chopin at Midnight, Chopin Behind Bars (Vol. 3, No. 6)

I listen to Chopin when I drive. My most recent find - all the etudes recorded by Louis Lortie (You Tube recording of Lortie ). The three dramatic ones at the end of Op. 25 are, as a set, a particular favorite. His timing is impeccable and the drama in the music well balanced with the classical perfection of form.

Another favorite CD that I recently returned to is of the two Piano Concerti with Krystian Zimerman at the keyboard, conducting his specially assembled orchestra - Polish Festival Orchestra. The clarinetist from that orchestra, Jan Jakub Bokun, has told me about the experience of rehearsing and playing with the Maestro. It was very strenuous, but immensely rewarding. One phrase, one detail, would take a long time to polish - sometimes aggravatingly long time. It had to be done to perfection... and it was. Just listen to the miraculous details - bringing out inner voices, phrasing, expression... Zimerman's Chopin is a true romantic, quickly moving from one emotional extreme to another, from enchantment to torment. An astounding vision of grand proportions. These are not little pieces of "stile brillante" provenance, ornamental, made to please. These are powerful expressions of the soaring human spirit.

OK, let's leave it at that. The spirit... What about the spirit? First, let me reflect on the spirit of Polish pride. To welcome the year 2010, just as I was finishing the "Chopin with Cherries" anthology that gave rise to this blog, I went to friends' house for a New Year's Eve Party. I never spent that time with this particular family and wanted to do something different, something I had not done before. It was interesting - filled with children and games, not serious adult dinner conversation and dancing.

But one dance captured my attention and remained in my memory: Chopin's Polonaise in A Major, Op. 40, nicknamed "The Military" (the link points to a YouTube recording by Maurizio Pollini). Yes, the same Polonaise that gave its first notes to a signal of the British broadcasts to occupied Poland during World War II. And here we are, dancing? Just after midnight all the guests at the party lined up in a long line of couples, the host sat at the grand piano and off we went. Around the living room, out onto the patio, up and down the steps, out one door, in another, all over the house... The moon was unusually bright that night, surrounded by an enormous halo, a portent of things to come. I felt a rush of pride, elation even, when we moved along with dignity, in triple meter: one long step with bended knees and two short ones. Down, up, up, down, up, up, around the house, around the world... It was so incredibly moving - a small group of Poles and their international rag-tag bunch of friends dancing to music written almost two hundred years ago and heard in so many homes, on so many concert stages. Welcome the new year, the year of Chopin! That was two years ago - and the tradition of dancing that particular Polonaise at midnight continues.

On the way back home, I drove through an unfamiliar neighborhood and saw boys playing with a bonfire on the front lawn of their small house. It was a working class neighborhood with tiny houses squished in neat rows on streets leading up to the hill of the Occidental College. The moon, the fire, the dance - I was inspired to write a haibun about it. It was recently published in an Altadena anthology, Poetry and Cookies, edited by Pauli Dutton, the Head Librarian of the Altadena Public Library:

Midnight Fire

In the golden holiness of a night that will never be seen again and will never return… (From a Gypsy tale)

After greeting the New Year with a Chopin polonaise danced around the hall, I drove down the street of your childhood. It was drenched with the glare of the full moon in a magnificent sparkling halo. The old house was not empty and dark. On the front lawn, boys were jumping around a huge bonfire. They screamed with joy, as the flames shot up to the sky. The gold reached out to the icy blue light, when they called me to join their wild party. Sparks scattered among the stars. You were there, hidden in shadows. I sensed your sudden delight.

my rose diamond brooch

sparkles on the black velvet -

stars at midnight

© 2010 by Maja Trochimczyk

I wrote more verse about the Polonaise itself, but all the descriptions fell short of the delight I felt that night, so it was reduced to just an introduction to a story that has no end. The contrast of warm flames and icy moonlight was unforgettable. I added the romance, of course - poetry is not supposed to be real, though, when rooted in an actual experience it touches a nerve in listeners. After one reading I was asked by an eager member of the audience: "So what about the man who gave you that brooch? Where is he now?" "There was no man. This is my brooch, I got it for my daughter and it returned to me," I said. There was nobody lurking in the shadows. . . The poem sounds better this way, though.

Fast forward two years, and I'm playing recordings of Chopin in jail. This is the path that I took, and this is where it is going. . . forward. My students are inmates who have completed the Sheriff's Education-Based Incarceration program, and are approaching dates of their release after completing their sentences. I do not ask what they are in for, it does not matter. What matters is that once released they never come back. Jailing them is a huge cost to society and committing crimes does not help them or anyone else. It is just not the right thing to do. But many offenders keep returning to jails, keep doing the same thing that they were always doing. My approach to changing their thinking, their image of self and the world, involves classical music. Chopin, in particular. Due to his serious illness, dying of TB, composing between fits of coughing and spitting blood, he can be an example of heroic courage. William Pillin expressed this idea very well, in his poem "Chopin" (included in the Chopin with Cherries anthology):

Chopin

(excerpt from a poem by William Pillin)

White and wasting he dotted

with splashes of blood his lunar pages,

carrying death like a singing bird

in his chest, his tissue held together

by dreams and bacilli. “I used to find him,”

wrote George Sand, “late at night at his piano,

pale, with haggard eyes, his hair almost standing,

and it was some minutes before he knew me.”

In Majorca, the doctors

shuddered at his blood-flecked mouth,

burned his belongings, compelled him

to take refuge in a former monastery.

“My stone cell is shaped like a coffin.

You can roar — but always in silence.”

When it stormed he wrote the ‘raindrop’ prelude

and from the thunder he fashioned an étude.

*

“I work a lot,” he wrote to his sister,

“I cross out all the time, I cough without measure.”

With death’s hand on his slender shoulder

he created ballades, études, nocturnes.

Chopin had what it takes to succeed against all odds. He used his time well - he created something lasting that speaks to us two hundred years later. They can do it too. It is heroic courage that is needed to succeed when you leave jail with a felony record, no friends to turn to (because those you had would bring you straight back to jail and those you hurt would not speak to you again), no home, no job...

America is very punitive. Not only does it have the highest rate of incarceration in the world: one in thirty one adults is under correctional supervision, well over 700 people per 100,000 adult residents. The second highest rate is in the second most punitive country, Russia. There, about 500 inmates are locked up per 100,000 of adults. Other countries have a fraction of that. The "war" of imprisonment was clearly won by the U.S. There are serious societal costs associated with that dubious victory. The stigma of having been once in prison or jail remains and permanently marrs the record of an individual who has virtually no chance for redemption. Job applications feature a box: have you ever been incarcerated, or committed felony, or misdemeanor? Once you check the box, the application lands in the garbage bin. I tell my students behind bars that they have to be really tough to ignore the rejections and insults that will come their way. Their sentences are finished but the stigma is there and will bring them back if they do not fight it by having the courage to be good.

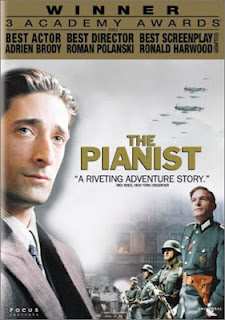

Chopin helps here. How? We listen to a Nocturne and then to the same Nocturne played by The Pianist's Adrien Brody in an old-fashioned suit. The camera pans out to show the engineer's booth. This is a live broadcast of the Polish Radio in Warsaw. This is September 1939. Soon the bombs begin to fall, the pianist initially refuses to stop playing but has no choice. He falls off the bench, the building is destroyed by German bombs, and his odyssey begins. The astounding, true story of survival against all odds - the story of Wladyslaw Szpilman, as told by Roman Polanski (another Holocaust survivor) leaves the incarcerated men I'm speaking to visibly shaken. The stellar beauty of the soaring Nocturne melody is cut down by the noise of explosions. War is evil, always evil. What did the musicians do to deserve their fate? What did the residents of Warsaw do to deserve being killed by German bombs? Nothing. War is a calamity that has to be survived. Living with the stigma of incarceration requires survival skills too. It requires a lot of courage - shown by the pianist in the film and the character's real-life model. It requires a persistent clinging to life, the good life.

I pan forward to another favorite scene in the film: the famous Ballade that Szpilman played for the German officer. This has to be one of the most famous music scenes in the whole history of film-making. When the can of pickles falls down from the pale, think hands of the starving musician and rolls to the feet of the uniformed German officer... when the gaze of the emaciated, long-haired pianist dressed in rags meets the eyes of the proud soldier... Then, the pianist begins to play and the Ballade takes them both on a journey. Away from destruction, away from hunger and suffering - somewhere else.

Here, courage and humanity triumph. The officer has to break his laws and his orders if he wants to save the life of the starving pianist. He does so, moved by Chopin's music that brought him back to the time when there was no war, only life and happiness. He must have heard such beautiful music at home, before the tragedy began. The extraordinary courage of the pianist, the compassion of the "enemy" and the drama of the music speak directly to the heart. Would the lesson stick? I do not know, I can only try to share it.

Is it worth my time? I hear comments: "lock them up and throw away the key." Not everyone behind bars committed, serious violent crimes and those who did would have been sent to the prisons, not jails. Once they did something wrong, paid the price for it and returned to the society "rehabilitated" - their sentences are supposed to be over and a new life is supposed to begin. But more often than not, it does not. They cannot find jobs, cannot earn a living, cannot function. Some are willingly returning to drug dealing or stealing. Others feel cornered, feel they have no option. If they do it the second time, the sentence will be longer, the return to the "narrow path" harder. I do not write it to excuse them. But it is important for them to know that they can stay on the "narrow path" of honest life, if they make some sacrifices, just like Chopin had to make sacrifices in order to continue to compose. What other option do we have?

Another favorite CD that I recently returned to is of the two Piano Concerti with Krystian Zimerman at the keyboard, conducting his specially assembled orchestra - Polish Festival Orchestra. The clarinetist from that orchestra, Jan Jakub Bokun, has told me about the experience of rehearsing and playing with the Maestro. It was very strenuous, but immensely rewarding. One phrase, one detail, would take a long time to polish - sometimes aggravatingly long time. It had to be done to perfection... and it was. Just listen to the miraculous details - bringing out inner voices, phrasing, expression... Zimerman's Chopin is a true romantic, quickly moving from one emotional extreme to another, from enchantment to torment. An astounding vision of grand proportions. These are not little pieces of "stile brillante" provenance, ornamental, made to please. These are powerful expressions of the soaring human spirit.

OK, let's leave it at that. The spirit... What about the spirit? First, let me reflect on the spirit of Polish pride. To welcome the year 2010, just as I was finishing the "Chopin with Cherries" anthology that gave rise to this blog, I went to friends' house for a New Year's Eve Party. I never spent that time with this particular family and wanted to do something different, something I had not done before. It was interesting - filled with children and games, not serious adult dinner conversation and dancing.

But one dance captured my attention and remained in my memory: Chopin's Polonaise in A Major, Op. 40, nicknamed "The Military" (the link points to a YouTube recording by Maurizio Pollini). Yes, the same Polonaise that gave its first notes to a signal of the British broadcasts to occupied Poland during World War II. And here we are, dancing? Just after midnight all the guests at the party lined up in a long line of couples, the host sat at the grand piano and off we went. Around the living room, out onto the patio, up and down the steps, out one door, in another, all over the house... The moon was unusually bright that night, surrounded by an enormous halo, a portent of things to come. I felt a rush of pride, elation even, when we moved along with dignity, in triple meter: one long step with bended knees and two short ones. Down, up, up, down, up, up, around the house, around the world... It was so incredibly moving - a small group of Poles and their international rag-tag bunch of friends dancing to music written almost two hundred years ago and heard in so many homes, on so many concert stages. Welcome the new year, the year of Chopin! That was two years ago - and the tradition of dancing that particular Polonaise at midnight continues.

On the way back home, I drove through an unfamiliar neighborhood and saw boys playing with a bonfire on the front lawn of their small house. It was a working class neighborhood with tiny houses squished in neat rows on streets leading up to the hill of the Occidental College. The moon, the fire, the dance - I was inspired to write a haibun about it. It was recently published in an Altadena anthology, Poetry and Cookies, edited by Pauli Dutton, the Head Librarian of the Altadena Public Library:

Midnight Fire

In the golden holiness of a night that will never be seen again and will never return… (From a Gypsy tale)

After greeting the New Year with a Chopin polonaise danced around the hall, I drove down the street of your childhood. It was drenched with the glare of the full moon in a magnificent sparkling halo. The old house was not empty and dark. On the front lawn, boys were jumping around a huge bonfire. They screamed with joy, as the flames shot up to the sky. The gold reached out to the icy blue light, when they called me to join their wild party. Sparks scattered among the stars. You were there, hidden in shadows. I sensed your sudden delight.

my rose diamond brooch

sparkles on the black velvet -

stars at midnight

© 2010 by Maja Trochimczyk

I wrote more verse about the Polonaise itself, but all the descriptions fell short of the delight I felt that night, so it was reduced to just an introduction to a story that has no end. The contrast of warm flames and icy moonlight was unforgettable. I added the romance, of course - poetry is not supposed to be real, though, when rooted in an actual experience it touches a nerve in listeners. After one reading I was asked by an eager member of the audience: "So what about the man who gave you that brooch? Where is he now?" "There was no man. This is my brooch, I got it for my daughter and it returned to me," I said. There was nobody lurking in the shadows. . . The poem sounds better this way, though.

Fast forward two years, and I'm playing recordings of Chopin in jail. This is the path that I took, and this is where it is going. . . forward. My students are inmates who have completed the Sheriff's Education-Based Incarceration program, and are approaching dates of their release after completing their sentences. I do not ask what they are in for, it does not matter. What matters is that once released they never come back. Jailing them is a huge cost to society and committing crimes does not help them or anyone else. It is just not the right thing to do. But many offenders keep returning to jails, keep doing the same thing that they were always doing. My approach to changing their thinking, their image of self and the world, involves classical music. Chopin, in particular. Due to his serious illness, dying of TB, composing between fits of coughing and spitting blood, he can be an example of heroic courage. William Pillin expressed this idea very well, in his poem "Chopin" (included in the Chopin with Cherries anthology):

Chopin

(excerpt from a poem by William Pillin)

White and wasting he dotted

with splashes of blood his lunar pages,

carrying death like a singing bird

in his chest, his tissue held together

by dreams and bacilli. “I used to find him,”

wrote George Sand, “late at night at his piano,

pale, with haggard eyes, his hair almost standing,

and it was some minutes before he knew me.”

In Majorca, the doctors

shuddered at his blood-flecked mouth,

burned his belongings, compelled him

to take refuge in a former monastery.

“My stone cell is shaped like a coffin.

You can roar — but always in silence.”

When it stormed he wrote the ‘raindrop’ prelude

and from the thunder he fashioned an étude.

*

“I work a lot,” he wrote to his sister,

“I cross out all the time, I cough without measure.”

With death’s hand on his slender shoulder

he created ballades, études, nocturnes.

Chopin had what it takes to succeed against all odds. He used his time well - he created something lasting that speaks to us two hundred years later. They can do it too. It is heroic courage that is needed to succeed when you leave jail with a felony record, no friends to turn to (because those you had would bring you straight back to jail and those you hurt would not speak to you again), no home, no job...

America is very punitive. Not only does it have the highest rate of incarceration in the world: one in thirty one adults is under correctional supervision, well over 700 people per 100,000 adult residents. The second highest rate is in the second most punitive country, Russia. There, about 500 inmates are locked up per 100,000 of adults. Other countries have a fraction of that. The "war" of imprisonment was clearly won by the U.S. There are serious societal costs associated with that dubious victory. The stigma of having been once in prison or jail remains and permanently marrs the record of an individual who has virtually no chance for redemption. Job applications feature a box: have you ever been incarcerated, or committed felony, or misdemeanor? Once you check the box, the application lands in the garbage bin. I tell my students behind bars that they have to be really tough to ignore the rejections and insults that will come their way. Their sentences are finished but the stigma is there and will bring them back if they do not fight it by having the courage to be good.

Chopin helps here. How? We listen to a Nocturne and then to the same Nocturne played by The Pianist's Adrien Brody in an old-fashioned suit. The camera pans out to show the engineer's booth. This is a live broadcast of the Polish Radio in Warsaw. This is September 1939. Soon the bombs begin to fall, the pianist initially refuses to stop playing but has no choice. He falls off the bench, the building is destroyed by German bombs, and his odyssey begins. The astounding, true story of survival against all odds - the story of Wladyslaw Szpilman, as told by Roman Polanski (another Holocaust survivor) leaves the incarcerated men I'm speaking to visibly shaken. The stellar beauty of the soaring Nocturne melody is cut down by the noise of explosions. War is evil, always evil. What did the musicians do to deserve their fate? What did the residents of Warsaw do to deserve being killed by German bombs? Nothing. War is a calamity that has to be survived. Living with the stigma of incarceration requires survival skills too. It requires a lot of courage - shown by the pianist in the film and the character's real-life model. It requires a persistent clinging to life, the good life.

I pan forward to another favorite scene in the film: the famous Ballade that Szpilman played for the German officer. This has to be one of the most famous music scenes in the whole history of film-making. When the can of pickles falls down from the pale, think hands of the starving musician and rolls to the feet of the uniformed German officer... when the gaze of the emaciated, long-haired pianist dressed in rags meets the eyes of the proud soldier... Then, the pianist begins to play and the Ballade takes them both on a journey. Away from destruction, away from hunger and suffering - somewhere else.

Here, courage and humanity triumph. The officer has to break his laws and his orders if he wants to save the life of the starving pianist. He does so, moved by Chopin's music that brought him back to the time when there was no war, only life and happiness. He must have heard such beautiful music at home, before the tragedy began. The extraordinary courage of the pianist, the compassion of the "enemy" and the drama of the music speak directly to the heart. Would the lesson stick? I do not know, I can only try to share it.

Is it worth my time? I hear comments: "lock them up and throw away the key." Not everyone behind bars committed, serious violent crimes and those who did would have been sent to the prisons, not jails. Once they did something wrong, paid the price for it and returned to the society "rehabilitated" - their sentences are supposed to be over and a new life is supposed to begin. But more often than not, it does not. They cannot find jobs, cannot earn a living, cannot function. Some are willingly returning to drug dealing or stealing. Others feel cornered, feel they have no option. If they do it the second time, the sentence will be longer, the return to the "narrow path" harder. I do not write it to excuse them. But it is important for them to know that they can stay on the "narrow path" of honest life, if they make some sacrifices, just like Chopin had to make sacrifices in order to continue to compose. What other option do we have?

Labels:

ballade,

Brody,

California,

Chopin,

jail,

Lortie,

midnight,

nocturne,

offenders,

poetry,

Polanski,

polonaise,

rehabilitation,

romantic music,

Szpilman,

The Pianist,

Trochimczyk

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Chopin's Revolutionary Etude in a California Jail (Vol. 3, No. 5)

On March 26, 2012, I started a new adventure - teaching a class on art and ethics to inmates of Pitchess Detention Center in Castaic, CA. I designed my four-part class as lessons in connecting feelings to thoughts, to teach virtues by using artwork, music, and poetry - a full range of artistic experiences. I called it EVA, or Ethics and Values in Art.

On March 26, 2012, I started a new adventure - teaching a class on art and ethics to inmates of Pitchess Detention Center in Castaic, CA. I designed my four-part class as lessons in connecting feelings to thoughts, to teach virtues by using artwork, music, and poetry - a full range of artistic experiences. I called it EVA, or Ethics and Values in Art.The core framework is provided by the Four Cardinal Virtues - courage, justice, wisdom or prudence and moderation, or temperance. Known since antiquity and used to teach moral values and character through over two thousand years of Western history, the virtues have largely been forgotten. Their presence in the lives of artists and their artwork is very strong, from Rembrandt to Chopin... In planning the classes I associated each virtue with an emotion - grief, shame, joy and calm - and with a moral action - compassion, forgiveness, generosity and gratitude...

While designing the curriculum, I thought I would be teaching women, so I was quite surprised when I was assigned to a men's institution. At Pitchess, they have been given a chance to think through their decisions and change their lives. The group I'm working with has decided to do exactly that. They enrolled in and graduated from the MERIT-WISE program, a part of the Sheriff's Education-Based Incarceration project. In some ways, these men have the best chance for a successful life after completing their "time out" to rethink their life choices and orientation.

In order to get ready for the challenges ahead, they participate in various workshops and classes taught by volunteers like me. The majority have never been to an art museum or a classical music concert. My goal is to help them find their way to the Hollywood Bowl . . . That and not to return to jail. How does one do that?

The Cornerstone

Justice:

Do what's right, what's fair.

Fortitude:

Keep smiling. Grin and bear.

Temperance:

Don't take more than your share.

Prudence:

Choose wisely. Think and care.

Find yourself deep in your heart

In the circle of cardinal virtues

The points of your compass

Your cornerstone.

Once you've mastered the steps,

New ones appear:

Faith: You are not alone . . .

Hope: And all shall be well . . .

Love: The very air we breathe

Where we are.

The framework I designed and teach right now is non-religious and, therefore, I skip the three Theological Virtues mentioned at the end of my poem. There is enough material for discussion, though, in the paintings of the Prodigal Son and Tobias by Rembrandt, Guernica by Picasso, City Whispers by Susan Dobay... There is enough inspiration in the Revolutionary Etude by Chopin and the Ode to Joy by Beethoven. If I put my own poetry in this context, am I acting grandiose and, as someone once called me (to my immense delight) - a megalomaniac? The point is to find yourself in your own words. I may "know" what's out there or what I've been taught, but I truly know only what I have experienced myself. I have to go deep inside, to the truth about me, to express a vision of the world that is both deeply personal and unique in my poetry.

The framework I designed and teach right now is non-religious and, therefore, I skip the three Theological Virtues mentioned at the end of my poem. There is enough material for discussion, though, in the paintings of the Prodigal Son and Tobias by Rembrandt, Guernica by Picasso, City Whispers by Susan Dobay... There is enough inspiration in the Revolutionary Etude by Chopin and the Ode to Joy by Beethoven. If I put my own poetry in this context, am I acting grandiose and, as someone once called me (to my immense delight) - a megalomaniac? The point is to find yourself in your own words. I may "know" what's out there or what I've been taught, but I truly know only what I have experienced myself. I have to go deep inside, to the truth about me, to express a vision of the world that is both deeply personal and unique in my poetry.Non Omnis Moriar

Only the best will remain.

Startled by beauty

I fly into the eye of goodness.

Only the best . . .

Wasted hours, words, signs,

Sounds and fake symbols.

Only:

Blue torrents of feeling

Crystallized in empty space

Twisted above our heads

Where light freezes

Into sculpted infinity

Oh,

If I could be there

Once

____________________________________

If only... To open their eyes and ears to new worlds, I take my students in blue prison garb on a wild tour of the most astounding creations of the human mind. The very first piece of music they hear is the "Revolutionary Etude" - Op. 10 No. 12, a lightning strike of a piece, designed to shake up and awaken... There applause at the end is intense. The majority has never heard anything like it.

One man said, "thank you so much! This is my most favorite piece in all music, in all the world." He had asked for Chopin in the previous class and was beyond himself with delight when his unspoken wish was answered. I asked him to explain the piece to the class and put it in context. He knew enough to talk about Chopin's rage at the war, Poland being attacked by Russia, the composer's loneliness in Paris. He also thought about expressing anger and other powerful emotions in art as a positive way of responding to something that is overwhelming and destructive. From the feeling of despair at the unfairness of the world and Poland's tragic defeat to an unprecedented masterpiece.

One man said, "thank you so much! This is my most favorite piece in all music, in all the world." He had asked for Chopin in the previous class and was beyond himself with delight when his unspoken wish was answered. I asked him to explain the piece to the class and put it in context. He knew enough to talk about Chopin's rage at the war, Poland being attacked by Russia, the composer's loneliness in Paris. He also thought about expressing anger and other powerful emotions in art as a positive way of responding to something that is overwhelming and destructive. From the feeling of despair at the unfairness of the world and Poland's tragic defeat to an unprecedented masterpiece. I did not ask, why, if he was so educated and knew so much, was he there, sentenced to jail... Everyone makes mistakes. Some more serious than others. My presence among the inmates is to help them use their time as a turning point, find a new path for the future. I use classical and romantic masterpieces to show criminals that they can and should remake themselves and live a different life. How different? Are they going to learn to play the piano and become Chopin experts? Not really, but they can learn from his courage, his fortitude. He composed while spitting blood, sick with TB since the age of 16. Suffering all his mature life, he died prematurely, but left for us timeless treasures.

Etudes are, in essence, practice exercises; they are designed to learn certain skills, solve particular technical problems - arpeggios, chordal patterns, layering of melodies, the use of specific fingers. Practice makes perfect. After 10,000 hours of practicing a skill, we may become experts in it, as Malcolm Gladwell assures us. That is another lesson for offenders serving their sentences. Moral character takes time and effort to develop. Even the least educated inmates in the Los Angeles County jail may be inspired by the perfection of Chopin's art, transforming a humble exercise into a perfectly structured and intensely emotional artwork that has and will survive the ravages of time.

Versions (Pollini's is my favorite):

Svatoslav Richter: extremely fast and apparently transposed a halftone higher, the image does not go with the sound

Stanislaw Bunin: not technically perfect, but immensely popular, 2:33

Janusz Olejniczak: The phrase endings are somewhat rushed, but the drama is immense! 2:33

Maurizio Pollini: as dramatic and tender as it has to be, with great climaxes, and a score to follow, 2:49

_________________________________

Photos from Big Tujunga Wash (c) 2012 by Maja Trochimczyk

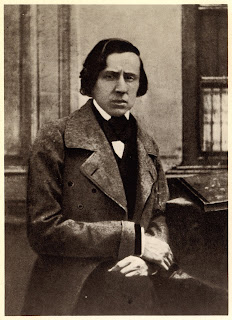

Chopin's last known photograph - daguerreotype by Louis-Auguste Bisson, 1849.

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

On Kocyan Playing Chopin and Liszt (Vol. 3. , No. 4)

When I first saw Polish pianist Wojciech Kocyan on the concert stage about twenty years ago, I felt he looked just like Fryderyk Chopin: frail, with longish dark-blond hair, sensitive, and sophisticated. Here was a pianist with great emotional and musical intelligence, a refined technique, and subdued charm. He excelled in the Mazurkas, but was equally fascinating in the repertoire of Debussy, Ravel and Skryabin. I felt that his well-thought out large-scale musical structures and his attention to expressive and textural detail made him a "pianist's pianist" - like Chopin himself who was thriving in salons of the aristocracy but abhorred crass and vulgar behaviors of the general public.

When I first saw Polish pianist Wojciech Kocyan on the concert stage about twenty years ago, I felt he looked just like Fryderyk Chopin: frail, with longish dark-blond hair, sensitive, and sophisticated. Here was a pianist with great emotional and musical intelligence, a refined technique, and subdued charm. He excelled in the Mazurkas, but was equally fascinating in the repertoire of Debussy, Ravel and Skryabin. I felt that his well-thought out large-scale musical structures and his attention to expressive and textural detail made him a "pianist's pianist" - like Chopin himself who was thriving in salons of the aristocracy but abhorred crass and vulgar behaviors of the general public. Over the years, I have invited Kocyan several times to play for events I organized, and I was always delighted with the charm and virtuosity he shared with his listeners, helping us make new discoveries even in well-known pieces. One outstanding appearance was not at a concert at all: Kocyan agreed to play a number of Chopin's compositions in-between readings of poetry from the anthology Chopin with Cherries.

The Ruskin Art Club event of May 2010 has remained in the memory of everyone in attendance. The fifteen or so poets who were present inspired the pianist and the pianist inspired the poets. Magic was in the air. In the elegant, old-fashioned interior of the Ruskin Art Club (a Los Angeles cultural landmark with over 120 years of history), we found ourselves in a 19th century salon. The interplay of profound, nostalgic, and romantic music with the spoken word remains unforgettable.

The Ruskin Art Club event of May 2010 has remained in the memory of everyone in attendance. The fifteen or so poets who were present inspired the pianist and the pianist inspired the poets. Magic was in the air. In the elegant, old-fashioned interior of the Ruskin Art Club (a Los Angeles cultural landmark with over 120 years of history), we found ourselves in a 19th century salon. The interplay of profound, nostalgic, and romantic music with the spoken word remains unforgettable. On Friday, March 9, 2012, we had an opportunity to witness another unforgettable event centering on Mr. Kocyan. His Faculty Recital at Loyola Marymount University's Murphy Recital Hall was a feast of music-making that revealed to me a side of Kocyan's talent I did not know well. After listening to his monumental interpretations of Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt I have looked for an appropriate adjective to capture my experience. The old-fashioned expression "a Titan of the keyboard" came to my mind - with its 19th century extravagance and uncanny accuracy.

Kocyan's appearance on the stage is hardly "Titanic" - he seems frail and delicate, like Chopin, not Liszt (and now with short-cropped hair). Yet, this is how the music sounded to my ears - majestic, awe-inspiring, sublime. The program followed a trajectory from an early Beethoven Sonata (in E-flat Major, Op. 7), through Chopin's Barcarole Op. 60 and Concert Paraphrase of Verdi's Rigoletto by Liszt, to a culmination in the latter's composer's masterly Sonata in B minor. Kocyan found the right tone for the various movements of the "Grand Sonata" (one of the longest written by Beethoven, exceeded only by the "Hammerklavier"). His virtuosity and technical prowess were obvious from the start of the Allegro molto e con brio and quite prominent in the second Allegro. The delicacy of feeling and graceful phrasing in the final Rondo were exceeded only by the emotional depth and structural flow in the second movement, Largo, con gran espressione . His program notes identified this movement as one of the greatest in all music, "overwhelming in the simplicity of means and the depth of its message."

Kocyan's appearance on the stage is hardly "Titanic" - he seems frail and delicate, like Chopin, not Liszt (and now with short-cropped hair). Yet, this is how the music sounded to my ears - majestic, awe-inspiring, sublime. The program followed a trajectory from an early Beethoven Sonata (in E-flat Major, Op. 7), through Chopin's Barcarole Op. 60 and Concert Paraphrase of Verdi's Rigoletto by Liszt, to a culmination in the latter's composer's masterly Sonata in B minor. Kocyan found the right tone for the various movements of the "Grand Sonata" (one of the longest written by Beethoven, exceeded only by the "Hammerklavier"). His virtuosity and technical prowess were obvious from the start of the Allegro molto e con brio and quite prominent in the second Allegro. The delicacy of feeling and graceful phrasing in the final Rondo were exceeded only by the emotional depth and structural flow in the second movement, Largo, con gran espressione . His program notes identified this movement as one of the greatest in all music, "overwhelming in the simplicity of means and the depth of its message." How would a simple gondolier's song, the Barcarolle, fit in this context? Surprise, surprise... in this most beloved Chopin's work, Kocyan revealed the "titanic" elements of Chopin's style that permeate many of his etudes, sonatas and scherzos. Under the pianist's fingers, the Barcarolle was neither sentimental, nor simplistic -he was able to structure the overall arch of dramatic flow of the music, reaching a climax of expressive passion. Having listened to a lot of nocturnes and mazurkas recenty (and just one astounding concerto, by Garrick Ohlsson with the Wroclaw Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Krzysztof Kaspszyk in February 2012), I was thrilled by the raw emotional power coupled with Olympian clarity that Kocyan brought out from this piece.

How would a simple gondolier's song, the Barcarolle, fit in this context? Surprise, surprise... in this most beloved Chopin's work, Kocyan revealed the "titanic" elements of Chopin's style that permeate many of his etudes, sonatas and scherzos. Under the pianist's fingers, the Barcarolle was neither sentimental, nor simplistic -he was able to structure the overall arch of dramatic flow of the music, reaching a climax of expressive passion. Having listened to a lot of nocturnes and mazurkas recenty (and just one astounding concerto, by Garrick Ohlsson with the Wroclaw Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Krzysztof Kaspszyk in February 2012), I was thrilled by the raw emotional power coupled with Olympian clarity that Kocyan brought out from this piece.As for Liszt, I never liked his "show-off" pieces of a three-ring-circus-master variety. The Rigoletto Concert Paraphrase certainly belongs among such magicians' tricks - pulling a rabbit out of a hat, or a complete orchestra out of a black-and-white keyboard. Kocyan's admirable technique was on display here - both in the velocity of his fingers, flying in a blur from end to end of the keyboard, and in the multiplicity of colors and textures he was able to create. The 19th century listeners had no recordings, no Ipods, no CDs, no music-in-the-cloud... After hearing an opera, they could experience it again only in transcription. Liszt's raised the bar of technical impossibility very high and shifted the attention away from the music or drama, towards the sheer mastery of the instrument.

I thought that this was the most difficult piece on the program, but Kocyan stated that the Sonata in B-minor was by far the most complicated and involved work that he had ever learned. And learn he did - the truly monumental (I'm running out of adjectives here) piece reaches the heights of elation when waves of sound wash over the whole concert all only to crush in the tragic darkness at the end. Kocyan deserves an award for the incomparable profundity of expression in rendering those dark chords more piercing and dramatic than any of the contrasts and upheavals that went on before it. Hopefully, the documentary recording will be made available. We are so lucky that music once played remains...

Born in Poland and a student of the legendary pedagogue Andrzej Jasinski (M.A. degree with the teacher of Krystian Zimerman) and the eminent John Perry at USC (DMA degree), Kocyan won his share of awards at piano competitions, including the Busoni, Fiotti, XI International Chopin Competition (special prize), and the Paderewski Piano Competition (first prize). He is notably at home in the recording studio and issued many CDs, on the Dux label.

In 2007, the Gramophone magazine chose his recording of Prokofiev, Scriabin and Rachmaninoff as one of 50 best classical recordings ever made. The Gramophone web site includes the following recommendation about Kocyan's Dux CD (no. 0389) with sonatas by Prokofiev and Skryabin, as well as Rachmaninoff's preludes:

In 2007, the Gramophone magazine chose his recording of Prokofiev, Scriabin and Rachmaninoff as one of 50 best classical recordings ever made. The Gramophone web site includes the following recommendation about Kocyan's Dux CD (no. 0389) with sonatas by Prokofiev and Skryabin, as well as Rachmaninoff's preludes:"Small label and unknown pianist deliver world-class artistry and first-rate engineering. Wojciech Kocyan not only stands ground alongside Pollini, Ashkenazy and Richter, but he also offers original insights that totally serve the music. If you see this disc, grab it."

Kocyan currently serves as the Professor of Piano at Loyola Marymount University and Artistic Director for the Paderewski Music Society in Los Angeles. His students are lucky, indeed... and so are his listeners. By the way, I had a close look at Kocyan's miraculous hands when turning pages for him at the Ruskin Art Club. I did not take any pictures this time, so all the illustrations are from 2010.

____________________________

Photos from An Evening of Poetry and Music - Chopin with Cherries reading at the Ruskin Art Club, May 2010. Kocyan at the piano, with Maja Trochimczyk and choreographer Edward Hoffman.

Cover of Kocyan's CD by Dux (Poland).

Monday, February 13, 2012

Chopin's Valentines and His Letters (Vol. 3, No. 3)

The association of Chopin's music with romance and love stories of all sorts is so profound that it is hard to imagine how mundane and trivial many of his own letters really were. He poured his heart in his music, and did not have to do it on the page. Instead, his letters are dedicated to ordinary matters, an equivalent of email or text messages of our times.

The association of Chopin's music with romance and love stories of all sorts is so profound that it is hard to imagine how mundane and trivial many of his own letters really were. He poured his heart in his music, and did not have to do it on the page. Instead, his letters are dedicated to ordinary matters, an equivalent of email or text messages of our times. In April I posted here an article about Chopin's letters. Excerpts are included below, to celebrate Valentine's day with Chopin. For this, we need some Valentine Day's music, so let us start with some links:

Nicknamed "La Tristesse," the Etude was completed on August 25, 1832 and originally envisioned in a much faster tempo than played in these recordings. Chopin's first tempo marking was that of Vivace, later changed to Vivace ma non troppo. Only for its French publication in 1833 was the tempo of the outer sections dramatically slowed down to Lento ma non troppo.

Newly arrived in Paris, Chopin was then at a threshold of an international career. He just signed agreements with French (Schlesinger), German and English publishers; was preparing his first major solo concert in Paris; and started giving lessons to music-loving aristocrats.

In Poland, he had been infatuated with a lovely singer, Konstancja Gladkowska. He was hoping to marry a daughter of a minor Polish noble, who shared his affections, but was rebutted in this plan by her parents. A sickly musician was not much of a prospect of a husband. Enter the love of Chopin's life, Baroness Aurora Dudevant, or George Sand, of a scandalous life-style, men's clothing, and interminable novels.

Nonetheless, the elan vital of his French novelist lover has revitalized Chopin. During the years with George he was extremely prolific. She adopted him into her household and took care of him like a mother. Her reward? He filled her home with divinely inspired music. Two centuries later we can enjoy it, too.

__________________________________________

The earliest Valentines that a child makes are for his/her parents. Chopin made colorful "laurki" greeting cards for his father and mother...

What did the boy say to his dad? The equivalent of "Happy birthday" and "I love you, Dad" - but in a more formal fashion, surprising for a six-year old. The lovely card was written for Nicholas Chopin's "Name-day" - a far more important celebration in Poland than that of a birthday. The Chopin family paid homage to their patriarch on the feast day of St. Nicholas, December 6 (1816):

Gdy świat Imienin uroczystość głosi Twoich, mój Papo, wszak i mnie przynosi Radość, z powodem uczuciów złożenia, Byś żył szczęśliwie, nie znał przykrych ciosów, Być zawsze sprzyjał Bóg pomyślnych losów, Te Ci z pragnieniem ogłaszam życzenia. F. Chopin. Dnia 6 grudnia 1816

Whereas the world proclaims the celebration of your Name-day, my dear Papa, thus it is also a great joy of mine, occasioned by the expression of heartfelt feelings, to wish you a happy life, that does not know sorrow, nor adversity, that is always blessed by God with good fortune, so these are, longingly expressed, my wishes. F. Chopin. On the 6th day of December, 1816.

If written by a child, and not dictated by his mother, older sister, or caretaker, these wishes surprise with the maturity of vocabulary and complication of syntax. What was Chopin's last letter, then? And how many letters did he write? This remains an issue of contention.

If written by a child, and not dictated by his mother, older sister, or caretaker, these wishes surprise with the maturity of vocabulary and complication of syntax. What was Chopin's last letter, then? And how many letters did he write? This remains an issue of contention. Scholars Zofia Helman, Zbigniew Skowron, and Hanna Wróblewska-Straus have been working for more than two decades on a fully annotated critical edition of all currently known Chopin's letters. The national edition of Korespondencja Fryderyka Chopina, issued by the University of Warsaw (available in Polish only) features not only detailed context of each letter, revised and defined placement in chronology, but also extensive notes about every single person mentioned in the letters or in any way associated with them. The hosts of summer vacations, the musicians and friends of musicians, the students and their families - all find their life-stories briefly noted. They were blessed and immortalized by their encounters with a genius whom the world does not want to forget. The one issue that makes it difficult to use along with older edition is letter numbering. The universally accepted numbering by Sydow has been changed, as new letters were inserted in the proper slots and those that were assigned to wrong dates or years, were moved to the appropriate point on the chronology.

The first volume, covering the years up to Chopin's departure from Poland and ending with the famous, tortured pages from his so-called Stuttgart Diary, written after Chopin heard about the end of the November Uprising (started in November 1830), with the fall of Warsaw to Russian troops on September 7, 1831. As the editors ascertained, the Stuttgart press published the first reports about these tragic events on September 16. The famous, dramatic and despairing monologue of an embittered exile was written partly before and partly after that date. Following von Sydow, it is customarily attributed to September 8, a day after the fall of Warsaw, but Helman and her team were able to argue for a more accurate date. After the outburst of despair, on September 18, 1831, Chopin left Stuttgart to continue his way on to Paris where he spent the rest of his life.